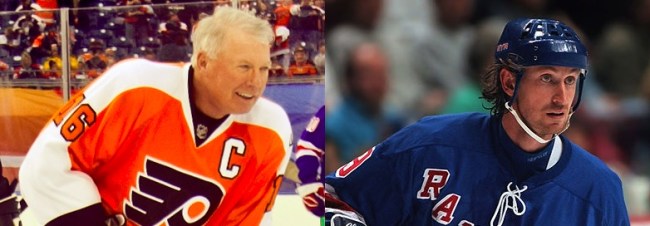

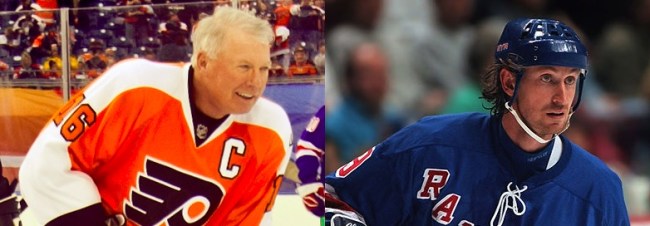

Left image by “Centpacrr“, Right image by “Hakandahlstrom” via Wikimedia Commons, both altered by author

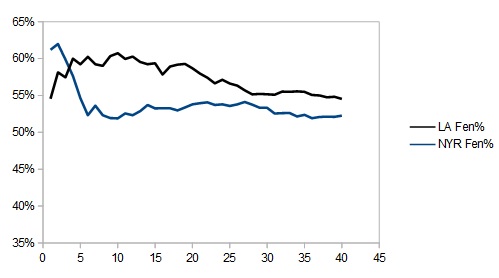

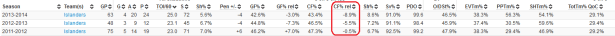

On December 30th, 1981, Wayne Gretzky’s Edmonton Oilers and Bobby Clarke’s Philadelphia Flyers met in a Wednesday night tilt rich with symbolism. Clarke, 32, was a couple of years away from retirement; two of his three remaining teammates from the Cup years, Reggie Leach and Bill Barber (defenseman Jimmy Watson was the third), were themselves out of the league in two years (Leach due to talent drop-off, Barber due to injury). Ironically, there was little indication in 1981 that this was going to happen – all were around 30, all were near point-per-game scorers playing all minutes. Whatever the case, they were the last of the Broad Street Bullies, and were now mentoring a new generation of “Bullies” like Ken Linseman, Tim Kerr, and Brian Propp, who seemed at times more annoying than dangerous. Though in transition, Philadelphia was still a great possession team (4th in the league in 2pS%, an historical possession metric), but fought the percentages all year to squeak into the playoffs. Edmonton, on the other hand, was romping through the league at record pace, and by December 30th held a comfortable lead over 2nd place Minnesota in the old Campbell Conference. Gretzky, of course, was at the heart of this surge, and by game 39 he had 45 goals.

The 1980s Oilers were the next step in NHL offense, really a Canadian version of the 1970s Soviet style of hockey. They didn’t need to bully their way to victories – they let the other team take the penalties, and skated all over them. I should say, that’s what Edmonton would eventually do; on this night they lined Gretzky up with Dave Lumley and Dave Semenko, as they had done most of the year. More on that later.

As I said before, though, the Flyers were a great possession team, as they always had been when Clarke and Barber were in their prime (they averaged, averaged, 55% 2pS% in the years 1973-74 through 1981-82, placing them consistently among the top 5 in the NHL). They were fast and calculating with their puck movement; the grit was just extra work – and who knows, maybe it contributed to Clarke, Barber, and Leach’s early retirement. The Bully when met with the Oilers, though, learned that the box was the bigger enemy.

Continue reading →