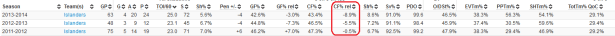

This dude didn’t drive possession much, but MAN what a shot.

Consider four types of forwards:

1. Forwards who don’t drive possession and don’t score points

2. Forwards who drive possession forward and score points effectively

3. Forwards who drive possession forward but don’t score points

4. Forwards who don’t drive possession but score points.

The first two types of forwards are easy to think about: Type 1 forwards are bad players, not really giving value through their play and Type 2 forwards are the best type of players, those who provide value in both offense and defense and aren’t a liability if they ever go on a cold streak.

Type 3 forwards are a little trickier, but really aren’t that hard to think about – they’re your ideal 4th and maybe 3rd liner, the guy who might not score but keeps your team in the game while your better guys rest.

Then you have your type 4 forwards – the dudes who can score a bunch of points but really don’t keep the puck out of your own zone and in the opponent’s zone. Perhaps these guys are really bad defensively, perhaps they’re completely inept in the neutral zone, or perhaps they’re guys who score mainly by being in front of the net at the right time, and thus aren’t really being helpful when the puck doesn’t come to them.

How do we value these guys? Depending upon the point totals these guys can put up, we can value them pretty high actually. Ilya Kovalchuk was a pretty damn good player who didn’t drive possession much, but his scoring almost certainly made up for what he cost the team otherwise. Matt Moulson’s hands allowed John Tavares to rack up assists due to his amazing ability to be in the right position to put in goals. Thomas Vanek likewise.

In a sense, these guys are basically role players. Of course, that role isn’t being a grinder or a checker or some other name for defensive forward, it’s to be an offensive specialist, paying little attention to anything else. You’d like to play these guys in positions that maximize that ability like any other role player – so high ozone starts, alongside guys who might complement those skills (playing them alongside guys who don’t have these weaknesses, and thus can make their line a plus possession line, is another typical way to handle these guys). And scoring lots of points is a pretty important type of role for a player to have.

Most of the time, the best scorers don’t fall into this category – the skills involved with being a plus possession player are the same ones that lead to scoring goals – getting the puck into the zone by carry-in, spending more time in the O Zone, etc. But a few guys will – think Ilya Kovalchuk or perhaps even the more recent version of Alex Ovechkin (though he used to be a clear driver of play). These are guys you play as much as possible despite the possession problems simply because well – scoring is what wins games in the NHL. These guys aren’t that common, so you’ll never see a low possession team dominate for multiple seasons like you did in the 80s (when three teams did accumulate such players). But you play them anyhow and you try and surround them with a lot of plus possession talent to make up for their shortcomings.

Again, these players aren’t bad by any means – they can even be elite! Of course, lacking possession driving skills means slumps by these guys will kill you, but for your Kovalchuk’s and Ovechkins, you’ll live with that.