Although published NHL salaries may seem exorbitant at times, players’ annual income is subject to a number of withholdings that limit their take-home pay. As we explained in Part 1 of this series, players lose some of their earnings to escrow – a reconciliation process arising out the Collective Bargaining Agreement between the league and the NHL Players’ Association. Another expense that reduces a player’s earnings is something that all workers in the United States and Canada are subject to: taxes.

Looking at the top 15 NHL salaries for the 2018-19 season and their net salaries for the year after taxes can show just how different those values can be. John Tavares headlines the list with a $15.9 million salary and a 53.3 percent tax rate, so his take-home pay after taxes is less than half of his salary, at just $7.4 million. On the low end, there’s Jamie Benn and P.K. Subban who only face federal tax rates, as they play in states without an income tax. Of the six players on this list with a $10 million salary for the season, Subban takes home the most after taxes ($6,334,310) since his effective tax rate of 36.66 is the lowest.

Teammates John Carlson, Evgeny Kuznetsov, and Alex Ovechkin have varying tax rates that are influenced by more than just their salaries, but where they reside. None of them actually live in Washington D.C., where residents are subject to steep tax rates; instead Carlson resides in Maryland (where he faces an effective state tax rate of 5.74 percent), while Kuznetsov and Ovechkin live in Virginia (with an effective state tax rate of 5.75 percent).

Given that wide range of tax rates between all 31 NHL teams, income taxes can be particularly influential on players. Besides the impact on take-home salary, these taxes can also influence where players sign and how a contract is structured. Governments levy and impose these taxes on an individual’s income. Not only do Canada and the United States levy a federal income tax, but a number of states, provinces, and cities do as well.

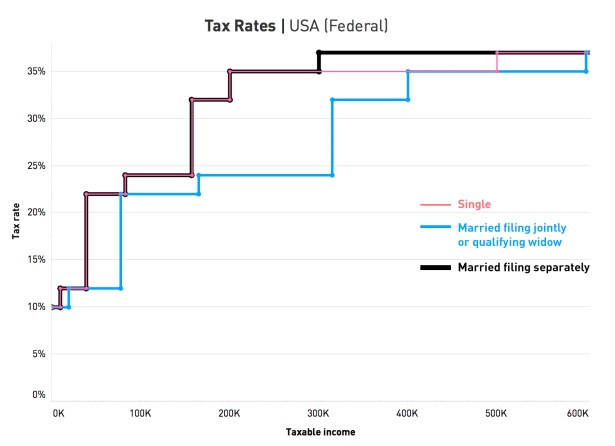

First, let’s delve into income tax in the United States. The actual tax rate varies between jurisdictions and can depend on a number of factors, including the earnings amount and how an individual files – whether they are single, married and filing separately, or married and filing a joint return. For minor league players, these tax rates can vary based on their salaries. The NHL’s minimum salary requirements ($575,000 for 2016-17 and $650,000 for 2017-18 and 2018-19), keeps players in the highest tax echelon regardless of their marital and filing status while they’re at the NHL level. But for those in minor leagues, their incomes may fit into brackets with lower tax rates.

The U.S. tax system is based on marginal tax rates that apply to income over set thresholds, or brackets. Each dollar you earn is taxed at the rate of the bracket it falls into. Those with income that reaches into the highest tax bracket will be subject to the taxes due on the lower income brackets first, and only the income earned above the final threshold will be taxed at the highest rate. So, a single filer that earns $500,001 or more a year first owes $150,689.50 – a culmination of all of the taxes for the lower brackets–– as well as 37 percent of their salary over the $500,000 threshold.

*Graphic created by Kikkerlaika

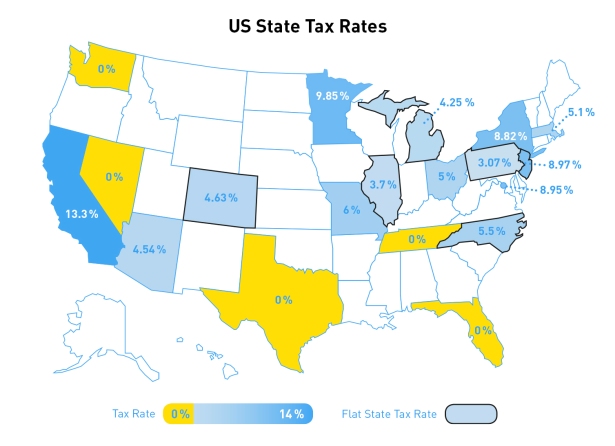

Along with a federal income tax, players are subject to state income tax. Some states have a variable tax rate, while others have feature a flat rate that all workers are subject to regardless of their earnings or marital status. Tennessee’s state income tax is unique from all others with an NHL franchise, as they only tax interest and dividends income at a five percent rate. As for the rest of the states with an NHL team that impose a tax rate, those rates are divided into brackets that vary based on annual earnings and filing status.

*Graphic created by Kikkerlaika

*Highest bracket shown for all states with income-based tax rates

Some states do not have income tax; those with NHL teams are Texas (Dallas Stars), Florida (Florida Panthers, Tampa Bay Lightning), and Nevada (Vegas Golden Knights). These teams have the most salary cap flexibility as a player receives more of their contract salary as take-home pay; a higher cap hit that is subject to state income tax could be equivalent to an untaxed lower cap hit. Washington state, where the NHL is expanding to 32 teams with a team in Seattle, does not have a state income tax either.

Not all players live in the same state or district that they play in, which can affect which state taxes them as well. Members of the New Jersey Devils may reside in New York City, which subjects them to New York’s state income tax rate. Players of the Washington Capitals may not live in the District of Columbia, and instead reside in Virginia like Alex Ovechkin does or Maryland like John Carlson does. Living outside of Washington D.C. and in Maryland and Virginia lowers the state income tax the player faces.

A number of cities also levy income or resident taxes, in addition to federal and state taxes. New York City, for example, has a 3.88% tax for residents that affects players on the Rangers, Islanders, and Devils that live in in the city. Since many members of the Islanders still reside in Nassau County and commute to Brooklyn rather than living in the New York City area, and many Devils live in New Jersey, they are not subject to that resident tax.

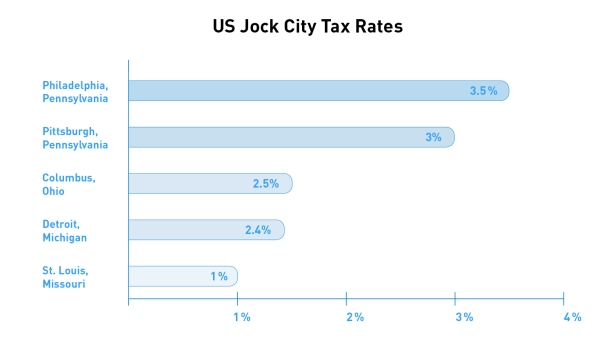

Besides New York City, Philadelphia (3.89%), Pittsburgh (1%), Detroit (2.4%), and Columbus (2.5%) all impose a city tax. Denver has a city tax as well, but it is a flat rate of $5.75 per month on compensation that exceeds $500.

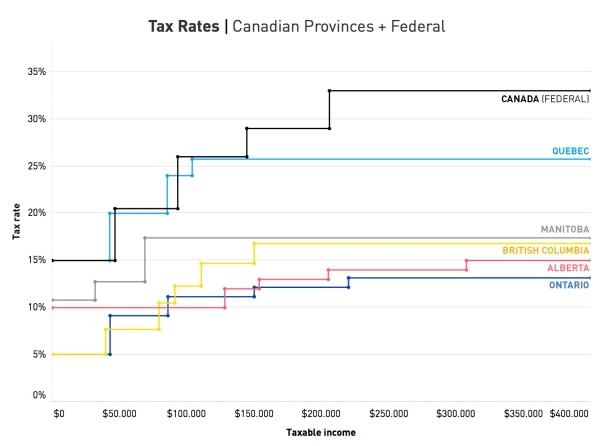

Canada, like the United States, has tiers for federal taxes. For 2018, 15 percent is taken out of $46,605 of taxable income. Then 20.5 percent is taxed on income that is over $46,605 up to $93,208, 26 percent on the next $51,281 (that’s between $93,208 and $144,489 in taxable income), and 29 percent is imposed on the next $61,353 up to $205,842. Lastly, any income over $205,842 faces a 33 percent tax rate.

Also similar to the United States are the taxes below the federal level. While the United States has state taxes, Canada has provincial taxes that may affect hockey players across the country. For the NHL, that’s in the provinces of Quebec (Montreal Canadiens), Ontario (Toronto Maple Leafs and Ottawa Senators), Manitoba (Winnipeg Jets), Alberta (Calgary Flames and Edmonton Oilers), and British Columbia (Vancouver Canucks).

*Graphic created by Kikkerlaika

Canadian provinces all tax in tiers like the federal government does, with certain rates being owed on varying segments of salary. All NHLers fall into these provinces’ highest level. Quebec’s top tier has the highest rate of provinces with an NHL team, as all earnings over $104,765 are taxed at 25.75 percent.

So, a player on the Maple Leafs or Senators would first owe the federal rate, then for the province of Ontario a 5.05 percent rate on the first $42,960 of taxable income, 9.15 percent on the next $42,963, 11.16 percent on the next $64,077, 12.16 percent on the next $70,000, and 13.16 percent on all income over $220,000.

The challenge for many NHLers is establishing where they are liable for resident income tax. American citizens are liable for American income taxes regardless of where their income is earned and where they live. Non-residents in the United States on the other hand, only owe taxes on source income, or income that is earned in the United States.

Many NHLers reside in two countries – like Canadian athletes that reside in their home country in the offseason and the United States for their home team during the season. Rather than being double taxed, there’s a tax treaty between United States and Canada to determine where resident income tax is owed. Tie-breaker clauses help determine the primary residency and establish tax liability. As long as an athlete of a Canadian franchise is not in United States (and vice-versa) for more than 183 days in a 12-month period, they receive tax relief from the Canada-US income tax treaty and aren’t double taxed – although they still may face jock taxes for those away games (more on that later).

How an athlete’s salary is taxed is also outlined in the treaty. Taxation on signing bonuses, for example, differs between countries. Since Canada considers signing bonuses to be a part of their total income, Canadian residents that receive those bonuses from Canadian franchises are taxed in accordance with their laws. However, the tax treaty limits the amount taxable for American players in Canada (and vice versa). These stipulations vary depending on whether they’re a resident of Canada, the United States, or are dual-citizens.

A number of states do not honor the federal tax treaty though. Those that apply to the NHL and do not follow the treaty are New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and California, so Canadian players in those states are still subject to taxation. Those players can claim the state tax as a foreign tax credit on their Canadian returns.

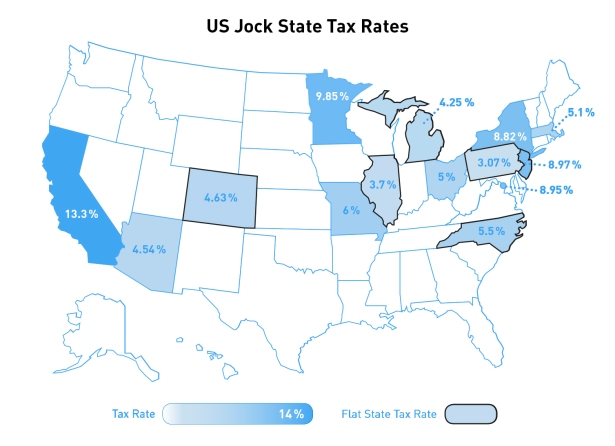

Players aren’t limited to federal, state, and city income taxes though, as they also face jock taxes – but these aren’t resident taxes, rather they are specifically designed to tax visiting workers. NHL players owe taxes in a number of states they visit and even some cities.

Non-resident taxes have been levied in a number of states for years. After the 1991 NBA Final between the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers, taxation of visiting athletes trended upwards and became a revenue stream for states and cities. These non-resident taxes in the United States and Canada aren’t limited to just athletes, but to the staff traveling with the teams throughout the season as well. Essentially, any non-resident workers that perform work from which they earn income are subject to these taxes.

Most states measure duty days to determine when these visiting athletes should be taxed. This includes practice days, along with game days, that are spent in that state (and city depending on whether that city levies a jock tax as well). To determine the duty days spent in each visiting state, the work days spent in the visiting state are divided by the number of workdays in a season, from preseason through the postseason.

Illinois only taxes visiting athletes if their home state taxes Illinois athletes when they play away games – so the Stars don’t owe the state of Illinois a jock tax when in Chicago because the Blackhawks aren’t taxed by the state of Texas.

*Graphic created by Kikkerlaika

Currently, the cities that include their own non-resident tax in NHL cities are Columbus, Detroit, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis.

*Graphic created by Kikkerlaika

As of March 2017, Detroit codified their jock tax to include travel days – even if those don’t include actually performing any work-related duties within the city – instead of limiting the tax to duty days. While their tax is not levied on income from signing bonuses, including travel days does increase how much they collect from athletes.

Pittsburgh levies a jock tax, called the “Non-resident Sports Facility Usage Fee.” It’s a three percent flat rate tax for non-residents that utilize a “publicly funded facility to engage in an athletic event or otherwise render a performance for which a non-resident receives remuneration.”

Tennessee had a jock tax, that has since been repealed. It was a flat rate tax of $2,500 per away game, that could not be applied more than three times in a tax year for visiting NHL and NBA athletes. Players that traveled with the team to Nashville, even if they didn’t actually play against the Predators, and were apart of their team’s roster for at least 10 days of the season, owed this city tax. The proceeds of this tax did not return to the state, but back to the state’s two professional hockey and basketball teams, the Predators and Memphis Grizzlies; in reaction to that, the NHLPA arranged a CBA provision that had the league pay this tax for the 2012-13 season. The following year, it was repealed by the state legislature and players were partially reimbursed for the taxes.

Canada does not levy a jock tax at a federal, provincial, or city level. The treaty between the United States and Canada generally protects all players on Canadian teams from jock taxes as well – except for in those states that do not follow the treaty. Those state taxes though, can be claimed on Canadian tax returns as foreign tax credits (via Gavin Management Group).

So how are players affected by all of this?

How players are affected by taxes has been magnified across professional sports over the years. In the NFL, jock taxes made headlines when the Super Bowl came to California in February 2016. Between the Super Bowl in Santa Clara, two in-season match ups in Los Angeles and Oakland, and practice and media days, Carolina Panthers quarterback Cam Newton owed the state of California approximately $137,000 in jock taxes for the year.

Taxes can also affect where a player lives in the offseason. A study conducted by the Department of Labor that was published in May 2014 identified that five times more professional athletes reside in the income-tax free state of Florida in the offseason than the national average.

Taxes can play a role in free agency for players across professional sports. More extremes have been seen outside of hockey, such as when Christian Yelich signed an extension with the Miami Marlins in 2015 that reportedly included a tax equalization provision to ensure that if he were to be moved outside of the no-income tax state of Florida that his take home salary wouldn’t be affected.

While not to the same degree as the MLB with Yelich, how taxes influence an NHL free agent has received attention as well. Before he signed an eight-year extension to stay with the Tampa Bay Lightning, the Tampa Bay Times explored how taxes might affect Steven Stamkos’s salary. Since the NHL has a salary cap, teams in states without state tax have the flexibility to offer a lower cap hit while maintaining the same take home, and the Stamkos situation demonstrated that.

The same conversation was had this past off-season about pending free agent John Tavares, who was contemplating leaving the New York Islanders for cities including San Jose which has the highest state tax in the United States, tax-free Dallas, and where he ultimately chose, Toronto.

And it may happen again with big name free agents like Artemi Panarin. If Panarin was looking for a contract with an annual salary of $12 million, he’d take home about $300,000 more if he stayed with Columbus than if he returned to Chicago. He’d lose over a million if he chooses New York over Chicago, but if he decided to go to Florida instead of New York, there would be about a $1.6 million increase in his take home. For teams with less cap flexibility, those numbers can make all the difference. Especially when there are teams without the burden of state taxes vying for the same pending free agent and the actual take-home pay is an influential factor in his decision.

As the MLB’s Yelich has exemplified, for some, that influence makes a massive difference. For others, like Tavares, it may be a consideration, but not what drives his decision. And for others, like Max Pacioretty in Vegas, it’s what makes a contract more cap-friendly since Montreal would have to pay him about $1.7 million more to have the same take-home pay.

A player’s NHL salary may seem high – and it is – but it’s not quite as high as it seems after losing a chunk to escrow and even more to taxes. Those deductions, at the very least, are always considerations that add more intricacies and wrinkles into an often already complicated contract process.

Thank you to Kikkerlaika for creating the data visualizations and Petbugs for editing this article.

This article is fucking amazing. If you ever do one on all the tax breaks given to NHL owners I hope I hear about it.

Ontario also has a surtax which is not accounted for here. I don’t understand it, but I think you could figure it out better than me lol. I’ve read that it starts making a difference around $100k in annual earnings.

Where are you getting those 2018-19 salaries? I can’t find any website talking about 15m salaries for anyone?

Do not forget that the players may also be subject to state, and local taxes, paid to the road team juridiction, for parts of their wages when they play on the road.

Except the “Nidgets” who wrote this article and then supplied information to it, didn’t take into consideration, tax free implications such as: Signing Bonuses (ex. Tavares, Matthews, McDavid, O’Reilly, etc). These kind of stories which are fabricated produce mis-info and mis-understanding. So, if you a player, receive over 90% of your salary as a signing bonus vs to be applied to escrow, essentially then, those players are further along then other players. The players association should have Kyboshed the entire issue, and then tackle the Mgmt/Owners, instead the players are set off against each other.

This article is grossly inaccurate. Each player must file income tax in every jurisdiction they play in. E for effort. Massive fail on execution.