Under the provisions of the collective bargaining agreement between the NHL and the NHLPA, a player’s cap hit and the salary they are paid can be two very distinct values in any given year. But even when you understand those differences, how much do NHL player actually take home?

Players’ actual earnings are diminished by a number of factors including escrow, agent fees, and taxes. Agent fees can range from 2-6% depending on representation agreements and services rendered. Tax rates vary throughout the NHL depending on the country, state, and city a team and player reside and play in. But of all the deductions from their income, escrow might be considered the greatest annoyance, as it’s a mechanism to ensure that the owners collect a greater share of hockey-related revenues (HRR) than they have in previous collective bargaining agreements (CBA).

So what is escrow, how much does it actually deplete a player’s salary, and why has it contributed to the tensions between players and owners?

First, let’s go through the basics about the salary cap and player earnings.

Before the start of an NHL season, the League projects the HRR for the upcoming season. That projection is split into two equal shares to be divided between the players and owners. The players’ projected 50% share is divided by the number of teams in the league (31 for 2017-18) to find the midpoint of the salary cap range. The upper and lower limits of the salary cap are then set by finding the values 15% above and below this midpoint. These limits establish the salary cap ceiling and floor, within which each team’s payroll must fit.

At the individual player level, the maximum salary is also set relative to the salary cap, and cannot exceed 20% of the upper limit ($14.6 million for 2016-17, $15 million for 2017-18). The minimum salary is adjusted on a set schedule: it was set at $575,000 in 2016-17 and boosted to $650,000 for the 2017-18 season.

How much a player earns each season and how much cap space those earnings take up are two different figures. Throughout the life of a contract, a player’s contract takes up a consistent amount of cap space, even if the actual salary varies from season to season. That cap hit is calculated as the average annual value (AAV) of a player’s contract. A player’s AAV is composed of total salary and signing bonuses divided by contract length.

There are two types of bonuses available in the Standard Player’s Contract (SPC): a signing bonus and performance bonuses. The signing bonus, even if spread over multiple years, is payable regardless of lockouts, buyouts, or a player’s on-ice accomplishments, while performance bonuses must be earned by meeting certain requirements over the course of a season. In practice, performance bonuses don’t count against the cap during the season because teams are allowed to go over into a 7.5% bonus cushion. After a season ends, all earned performance bonuses are counted against a club’s averaged salary, and could result in a cap overage penalty that is applied the following season.

So where does escrow come in?

Even within a hard salary cap system such as the NHL’s, the salary spend can vary significantly across teams. How much teams spend in actual salary has a direct impact on how the league’s revenues are split: if more teams are closer to the cap floor, the players may not receive their full share of HRR. On the other hand, if all teams are closer to the cap ceiling, the players may receive more than their share of revenue.

To ensure that the revenue is equally split between players and owners, some sort of process is required to reconcile anticipated discrepancies. Payments are collected from the players in case of those shortfalls in revenue; that process, as outlined by the Collective Bargaining Agreement, is escrow:

“The NHL and NHLPA agree that each Club may, in accordance with Section 50.11 of this Agreement, withhold a certain percentage of each Player’s Player Salary and Bonus obligations throughout each League Year and that such funds, if any, shall be held in an Escrow Account so that in the event that the NHL Clubs spend, on an aggregate basis, more or less on League-wide Player Compensation than the Players’ Share in a particular League Year, then pursuant to the Reconciliation and Distribution Procedures, the funds in the Escrow Account shall be distributed to the League or Players as described herein.”

Essentially, the league collects a percentage of player salaries into an escrow account throughout the season. All active players still under a Standard Player Contract are subject to this collection. The rate that is collected is determined at the start of the regular season and is subject to three adjustments, at the conclusion of the first-, second-, and third-quarters of the season.

Teams withhold the specified amount of a player’s cumulative salary and bonuses in each pay period (players are paid on a bi-weekly basis, which equates to 12 paychecks a season), that is calculated by multiplying a player’s earnings by the applicable escrow percentage for that period. Escrow is not directly deducted from a signing bonus payment though, the amount due from those bonuses is taken off salary payments throughout the season.

Escrow funds are still withheld on buyouts, but not on deferred salary or deferred bonuses. Performance bonuses are assessed separately, and escrow deductions are made based on the likelihood of them being earned.

Throughout the season, escrow continues to accumulate; then, at the end of the season, the deviation between the projected and actual HRR is determined so that funds held in escrow can be dispersed to the players or the owners such that a 50/50 split in revenue is achieved.

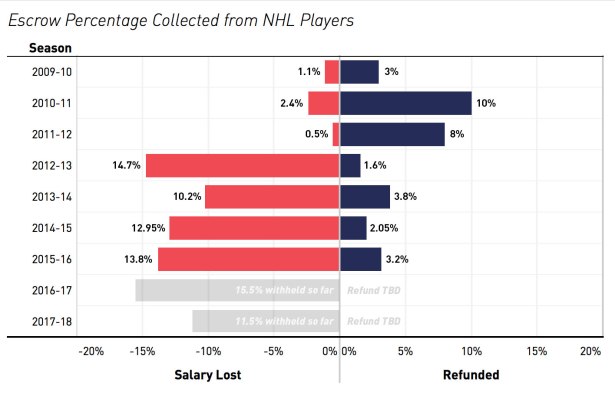

*Graphic created by Kikkerlaika

The table above shows the amounts deducted for escrow as well as the refunds after actual revenues and salaries were reconciled going back to the 2009-10 season. The most notable change in escrow rate was during the 2012-13 season, when the rate withheld increased from 8.5 to 16.3%. Players had lost 0.5% in 2011-12 before losing 14.7% of their salaries the following year. This significant change coincides with the 2012 lockout and the current CBA being implemented; that CBA decreased the players 57% share of HRR to 50%, so player salaries had to somehow be brought down while maintaining the face value of existing contracts. Consequently, a greater escrow percentage had to be deducted to from the players’ salaries.

Only 2.05% of the 15% of players salaries collected in 2014-15 was refunded to the players. Steven Stamkos of Tampa Bay Lightning was in the fourth year of his $37.5 million contract in 2014-15. While he had a $7.5 million cap hit, escrow was deducted from his $8 million salary (all base salary, no signing bonuses). Originally, $1.2 million was withheld. After receiving a 2.05% refund, he ended up losing just over $1 million to escrow clawbacks.

The 2015-16 season saw the highest escrow withholding of 17%, yet only 3.2% was refunded, resulting in the players losing the highest percentage of salary yet: 13.8%. Stamkos was in his fifth and final year of his contract and his total salary decreased to $5.5 million. He lost $759,000 of his salary to the 13.8% escrow deduction.

During the 2016-17 season, 15.5% was withheld. Next year, after the final revenue count on that season is completed, the refund will be calculated and announced; already, that projection has been estimated to be between 2.5 and 3%.

The 2016-17 season was the first year of Stamkos’s eight-year, $68 million contract extension. This contract was structured differently than his last, as the majority of his salary consisted of signing bonuses. That year, $8.5 million was paid in signing bonuses, while his base salary was only $1 million. Until the NHL establishes the escrow refund for that season, over $1.47 million has been withheld from that season’s salary.

For this season, the first-quarter escrow rate was announced as 11.5%, which is the lowest since 2011-12. The rate has remained constant for the second and third quarters. Small salary cap increases can help facilitate a lower escrow rate; since there was only a 1.6% growth factor to the salary cap, the amount ultimately withheld (after refunds) should be lower for the players this season – at least, according to Commissioner Gary Bettman.

At this season’s Board of Governors meetings in December, Bettman said: “We’re projecting from our standpoint that the final escrow when it’s settled out and we disperse it will be a single-digit escrow from player salaries for last season… For this season, if we stay on the low end [of the cap], we can keep it single digits as well.”

Escrow is a point of contention between players and owners, and the refunded percentage being so insignificant puts even more pressure on the issue. But owners are adamant in keeping this provision in the next CBA. The NHL denying their players the chance for the Olympics in 2018, then asking the players not to opt out of the CBA in 2019 in exchange for Olympic participation, only furthered the existing tensions. As a result, the league and players are both gearing up for a lockout, and it’s been reflected in how players are structuring their contracts. Players are increasingly negotiating for larger signing bonuses for 2020-21 season, which would be paid before a lockout begins. The league has tried to shift the blame for escrow costs, as exemplified by Bettman alleging that if the Players’ Association had a “contrary view” on revenues, the players would be the beneficiaries of a more significant refund.

Since the NHL instituted a salary cap in 2005, escrow has been a mechanism to reconcile payments from players to ensure hockey-related revenues are split according to the agreed upon share. Some sort of reconciliation process is necessary as long as there’s a fixed split of revenues that has to be met. Taxes, on the other hand, are an inevitable cost in Canada and the United States; between federal, state/provincial, city income taxes, and jock taxes, it can get complicated. Stay tuned for Part 2, where we delve into taxes to further break down how much a player actually earns.

I wonder:

If the players were to agree to a modest base salary (for example, $500, 000US in the States, $500, 000CAD in Canada), would it not be easier for the owners to pay the players more money by distributing profit(s) according to each player’s achievement(s) at various stages of the regular season (and, in 16 of 31 cases annually, the playoffs)?

I suspect that this would take pressure off the owners and serve to motivate the players themselves…a glorified version of the ‘piecework’ concept developed by Henry Ford ages ago, when the N.H.L. was yet to be realized.

Somehow, I think that it will work best; this way, each individual market will survive on its respective own, and players league-wide will simply have to accept the differences (Buffalo and Edmonton players will probably not earn as much outright as Colorado, Toronto and Chicago players, but the Western New York and Northern Alberta teams may very well outperform the aforementioned groups).

Canada vs United States is not the same amount of money if you change Canada money to US money you have to pay extra because US money is worth more

I have noticed you don’t monetize your blog, don’t

waste your traffic, you can earn additional bucks every month.

You can use the best adsense alternative for any type of

website (they approve all websites), for more details simply

search in gooogle: boorfe’s tips monetize your website