Hits. Long-forgotten when it comes to hockey analytics and for good reason. It’s been established in many places, even on this site by Garret Hohl, that how often you hit your opponent carries little worth when it comes to predicting goals. Sure, there will always be a play here or there that works out, but by and large hits are noise. Yet, that doesn’t stop teams from shelling out big money for players that can score and hit, despite all evidence to the contrary that the latter is noise. So, why bring it up? Well, someone retweeted this into my timeline Wednesday night and I couldn’t get it out of my head.

This idea that a “significant reason” why the Oilers signed Milan Lucic was because he will retaliate against the opposition if someone takes liberties with Connor McDavid is a perfect sound bite for fans. That’s what they want to hear. He’s got 97’s back. And, I agree with the follow-up tweet from Japers’ Rink, that deterrence is impossible to measure save for anecdotally.

Every Buffalo Sabres fan remembers when Lucic did this to Ryan Miller. Or, once he came back from injury, what Jordin Tootoo did a few weeks later. The organization’s response? The next summer, they go out and sign John Scott to toughen up the team and act as a deterrent in direct response to Lucic’s hit on Miller.

So, naturally, this got me thinking that if this is true – Lucic or Scott deters the opposition from hitting or taking penalties against start players – it should show up in their drawn hit rates, right? After all, if players are making a conscious decision to not hit a star player due to the fact that Lucic, Scott, Tanner Glass, Zac Rinaldo, et al are in the opposing lineup that night, we would expect to see fewer hits made against them.

It just doesn’t happen because this is a myth.

Ryan Wilson wrote about this last season, specifically regarding Glass. Below is a clip courtesy of Gif-Master @MyRegularFace from the incident mentioned in Ryan’s post: Glass informs Rinaldo to stop running his teammates or he’ll have to answer to him. Seconds later, Rinaldo runs a Ranger. That’s some deterrent.

https://gfycat.com/LiquidEnragedAmbushbug

The Numbers

Anecdotal evidence aside, where we should see some impact is in the hits made against each player with and without the deterrent on their team. I asked Micah Blake McCurdy for this data since the NHL – shockingly – doesn’t keep anything of use on their website.

I decided on using some of the bigger names, namely Lucic, Scott, Rinaldo, & Glass, as Lucic is what gave me the idea to look into this and the others are still active (well, at least they were until one was made an All-Star, but that worked out for him in the end) and looking at the rate at which their teammates are hit (Drawn Hits/60) in the year prior to the deterrent joining the team, the year(s) he was on the team, and then the first year after he left. So, this means we’re looking at players from the 2014 – 2016 Boston Bruins, the 2014 – 2016 L.A. Kings, the 2014 – 2016 Philadelphia Flyers, the 2012 – 2014 Pittsburgh Penguins, the 2014 – 2016 New York Rangers, and the 2011 – 2014 Buffalo Sabres. Each player had to be on the team in multiple seasons and had to play more than 200 minutes in each season.

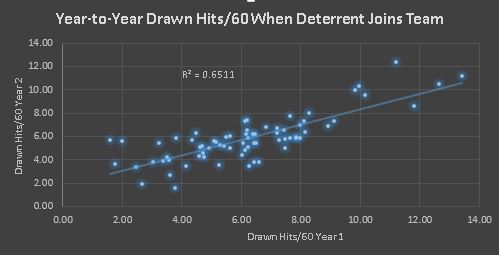

Here we see that in the season prior to one of those four named players joining the team, a player’s drawn hits/60 predicts what their hits will be once the deterrent is on their team quite well. Now, let’s look at the final year the deterrent is on the team and how well that drawn hit rate predicts their hits once the deterrent leaves.

Virtually the same. Whether the deterrent joins or leaves the team, the rate at which a player is hit predicts future hit rates about 63% – 65% of the time, given this sample.

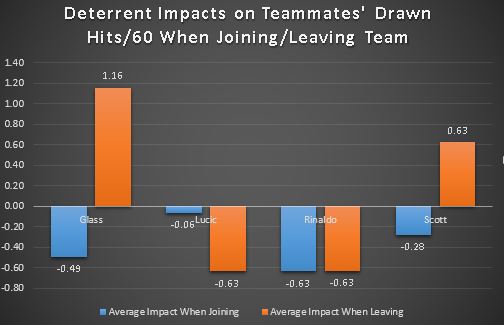

We can also look at how each deterrent impacted their teammates specifically by looking at the rate at which their teammates average drawn hits/60 changed when he joined and left the team.

So, based on this, Tanner Glass’ Penguins teammates were hit 0.49/60 less often once he joined the team and 1.16/60 more often once he left the team. These are incredibly small rates, so how does that work out? Well, say a player is on the ice for fifteen minutes of 5v5 hockey in a game. Those Penguin players were, on average, hit one less time every eight games once Glass joined than they were the previous season. Once he left, those same Penguins players were hit about one more time every four games.

Looking at this, Glass and Scott’s teams were hit more often once they left, whereas Lucic and Rinaldo’s teams were hit less once they left. There’s a little bit of overlap with Lucic and Rinaldo, but I thought it was interesting to include given that Rinaldo did a “better” job of deterring hits than Lucic.

In the end, none of this matters.

Conclusions

This is about what we’d expect. This is only one method of looking at this, but it seems like there should be something of note here if this anecdotal wisdom is to be true. There is an impact, but it is so incredibly small: a player will see about one less hit every twelve games (looking at the average across all players), or between six and seven across a full season. Maybe those are the “really bad” hits that players won’t attempt because there will be “retribution”or some other vague juvenile concept, but it simply doesn’t add up.

So what? How can we use this? Well, if you’re considering signing or trading for a player, you should absolutely not let the thought that their presence alone will stop the other team from taking runs or hitting your star players enter your decision-making process. You sign or trade for players because they can help you score goals, not because you think you need someone to “police” the opposition. Lucic does have other uses, but any GM that signs Glass, Rinaldo, or Scott and says “This helps our team” with a straight face needs to have their phone turned off and “promoted” to a special assignment position within the organization. Anytime a team can avoid using bad information to make a decision is a win for them.