The results of score effects are pretty basic hockey analytics knowledge at this point. Teams down in goals tend to take more shots, while teams up tend to take less, with the effect becoming larger as the game goes on.

We often explain this effect by saying teams go into a “defensive shell”, playing extremely conservative on offense to avoid easy opponent scoring opportunities, at the cost of more time in the team’s defensive zone. It is of course, not a one team effect either – we often emphasize that the other team is taking greater risks as well to try and score, which is why the shots taken by the team with the lead go in at a higher rate than normal. That said, it’s pretty much accepted that going into a shell would be a losing strategy for a team to attempt over a whole game, which is why teams don’t attempt this strategy for a full game.

So if we consider the shell a losing strategy, why do teams go into the shell even in the third? David Johnson had a great article on this here, explaining that even if the Defensive shell results in a team being outplayed more than their normal strategy, it still can make sense:

For some people this may not make sense intuitively. How can it be better to stop playing a system in which you are expected to out score your opposition and start playing a system in which you are expected to score the same as your opponent. The reason is simple and it comes down to that over a short period of time your are essentially dealing with small sample size issues and randomness becomes more important than long term skill. The reality is, over a short time one team is almost as likely to score as the other so which team scored next is close to random, if any team scores at all.

The most important thing when protecting a lead is simply reducing the likelihood that your opponent will score because the cost of your opponent scoring is far greater than the benefit if you scoring (it is irrelevant whether you win 3-1 or 2-1, a win is a win in the standings).

You should definitely read the article in full, but the quote above gets at the key point: If the defensive shell reduces the rate of scoring for the opponent, it makes perfect sense for a team to go to it in the last few minutes, even if it results in being outplayed.

Here’s the problem: the Defensive Shell doesn’t reduce the rate of opponent scoring. It actually INCREASES it.

It’s pretty well known that the defensive shell increases the rate of shots against but the tradeoff is supposed to be allowing more perimeter shots instead of high quality chances, lowering the opponent’s shooting %. But, as noted by Petbugs/Graphic-Comments in a post on score-adjusted PDO, what happens is actually the opposite:

That’s right, when trailing, teams’ shooting percentages actually increase marginally on average. The effect is small, but at the very least it’s clear that shooting % does NOT drop when a team is behind, despite them taking more shots.

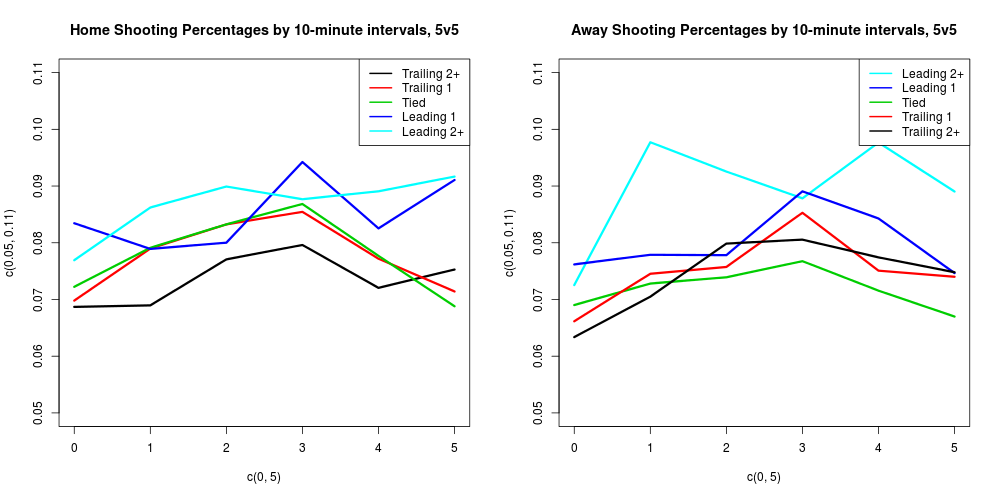

Perhaps shooting % drops when behind later in games? After all, score effects become more pronounced as we get later and later in the game, particularly the third period? The answer, courtesy of A.C. Thomas is….nope:

Yeah pretty much at every point in the game, INCLUDING in the final minutes, a trailing team’s shooting percentage is equal to or greater than teams’ shooting percentages while tied. Shooting percentage DOES drop late, but the effect isn’t due to score effects – the same drop happens while tied (I’d guess this is a fatigue effect). The end result is obvious: teams score more frequently when BEHIND than when tied or up late:

Yeah, so the defensive shell does the exact OPPOSITE of its intended design – rather than decreasing the rate of scoring, it INCREASES it by a good margin (this is presumably why comebacks feel like they happen so often).

Conclusion:

So why does the defensive shell still exist? Well, for one, it SOUNDS like a good idea in theory. If it did indeed reduce the rate of scoring, it would make total sense to execute. Moreover, there are probably psychological reasons as well – leading late in a game, no one – not the coaches or the players – wants to take any actions which could be construed as risky, which could possibly result in the tying goal against. As such, NHL coaches preach being defensive and players play conservative, and the defensive shell lives.

For this reason, it’ll probably never be the case where the defensive shell is eradicated from hockey – players and coaches will always be risk averse late with the lead. But the more and more they can get away from the shell, the more games they will win.

One of the freakonomics books (How to think like a Freak afaik) broke down why soccer players shot penalty shots to the left or right, not the the centre. The highest shooting percentage happens to be balls shot at the centre of the net, but if the shot happens to be saved, the shooter looks like a fool. Better to shoot to the outside and lower the shooting percentage a bit, just to look like you gave it your best.

It’s risk aversion of course, and like you said, risk aversion that limits how bad you look if indeed a mistake occurs.

Defensive shells do work – the opposition scoring rates are reduced compared to earlier in the game in the same game state.

It seems like you’re making an argument about goal difference, while Johnson made clear that the focus was on reducing opposition scoring rates, despite the greater impact it would have on your own offence.

You are not reading the data correctly. Scoring goes up for teams when down, even late, when compared to how teams do when tied.

The change in scoring rate as time goes on is due to fatigue, not the defensive shell, as teams have no reason to shell when tied until the last few minutes

My post was a look at the theory, not whether it is practical. Unfortunately it is next to impossible to take a practical look because it is next to impossible to isolate the defensive shell for the leading team from the aggressive offense of the trailing team. Who is to say that if the leading team didn’t go into a defensive shell goals wouldn’t be scored at an even higher rate.

I have also shown that coaches probably aren’t that great at identifying good defensive players (http://hockeyanalysis.com/2013/09/14/are-coaches-any-good-at-identifying-defensive-players/) so the uptick could be that the trailing coach is better at putting good offensive players on the ice than the leading coach is at putting good defensive players on the ice.

I enjoy, lead to I found exactly what I was having

a look for. You’ve ended my 4 day lengthy hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day.

Bye